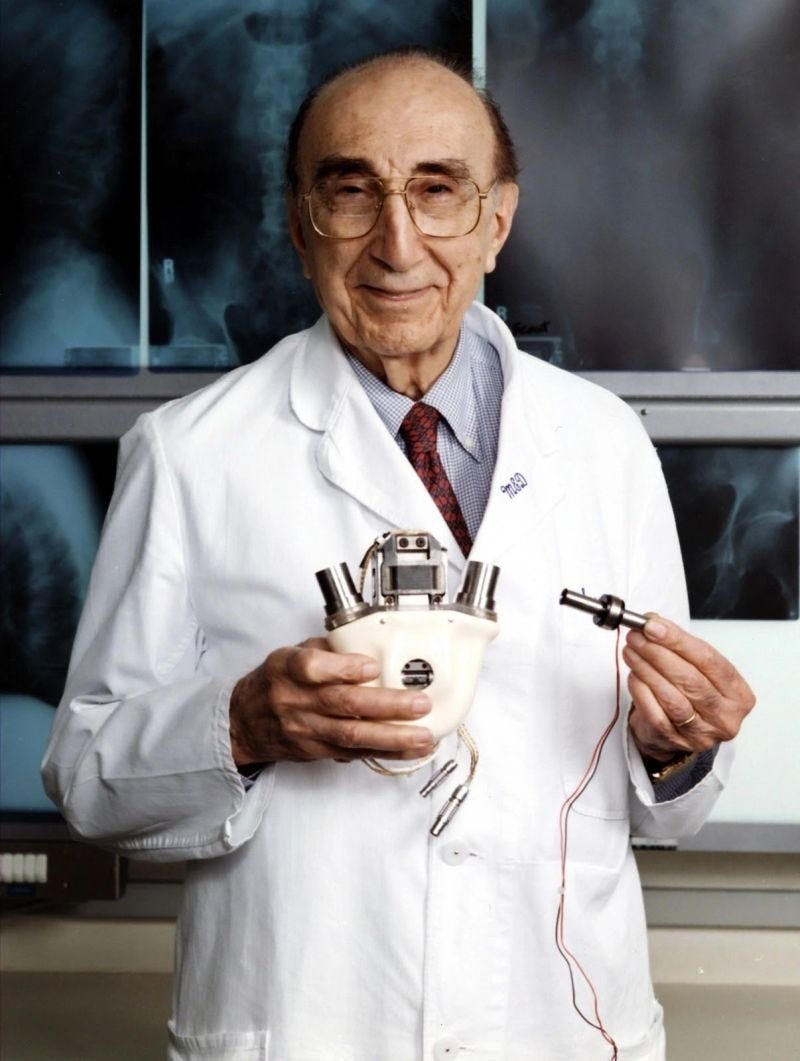

Michael DeBakey did not wait for the future of medicine.

DeBakey Made It

Michael DeBakey did not wait for the future of medicine.

When Michael DeBakey picked up a length of Dacron fabric in a Houston department store and told the clerk he needed it to rebuild a human artery, the man laughed. DeBakey did not. He walked out with the material because he knew the future of vascular surgery depended on something no manufacturer was willing to supply.

DeBakey lived in a world where medicine still surrendered to limits.

Heart patients died in operating rooms because surgeons did not yet have the tools or the techniques that could keep them alive.

DeBakey refused to accept that.

He believed the body could be repaired the same way a craftsman repaired a delicate machine: with precision, invention, and calm hands.

He designed a roller pump at 23 years old, a device that later became a core component of the heart-lung machine.

It kept blood moving outside the body during surgery, a breakthrough that opened the door to procedures once considered impossible.

Surgeons around the world adopted it.

DeBakey treated it as only the beginning.

In the 1950s, when no company produced grafts strong enough to replace damaged arteries, he went to a store, bought Dacron fabric, brought it back to the lab, and stitched prototypes on a sewing machine.

He tested them, refined them, and implanted them successfully.

Patients who had once been given weeks to live left the hospital walking upright.

Then came the era of open heart surgery.

DeBakey performed some of the first aortic aneurysm repairs ever attempted.

He operated on soldiers, senators, and ordinary people who arrived at the edge of death.

His team described his focus as almost unnerving.

He moved with a steadiness that made the room feel anchored even in moments when the stakes were measured in seconds.

In 1966, he helped develop the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital units.

Those MASH units brought advanced surgical care closer to the battlefield and dramatically increased survival rates.

DeBakey saw war not as a theater of heroism but as a place where medical innovation had to move faster than destruction.

He advised presidents.

He chaired committees that reshaped medical education.

He built one of the world’s leading cardiac surgery centers at Baylor University in Houston Texas.

Surgeons clammered to train with him despite grueling hours and tasks. There was a limited number of fellowships available each year. The competition to gain favor with him was enormous. A Debakey Fellow gained the power to have hospitals fund new departments. Many current heart programs initially were funded by his seeding the ranks of heart surgeons.

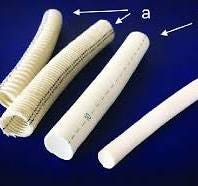

Cardiovascular surgery has advanced immeasurably since then, but Dacron patches (polyester) are still widely used in vascular surgery, especially for carotid artery surgery and complex aortic repairs.

Dr. Michael E. DeBakey developed functional Dacron vascular grafts in the early 1950s, creating them from synthetic fabric to repair blood vessels, with the first successful implant in a patient occurring in 1954 at the Houston VA Medical Center. He famously stitched the first prototypes on his wife’s sewing machine, making effective treatment for aneurysms and aortic dissections possible.